Leo Harris (second from left in photo) joined 611 squadron in the spring of 1942 and flew Spitfires from Kenley and Biggin Hill on missions over occupied France. His best pal was my father Flight Sergeant Tom Whitfield (far left in photo).

After a one year tour of duty they were both promoted to Flying Officer and posted overseas to Gibraltar. On 23rd August 1943 Harris was on a low level patrol hunting for enemy submarines when his Spitfire suffered engine failure. Too low to bale out, he ditched into the Mediterranean Sea and his plane disappeared beneath the waves.

Thirty five years later my parents went to Malta on holiday and visited the magnificent RAF memorial. It lists more than 2,000 airmen who were lost over the Mediterranean and my father was shocked to find Harris's name. He wrote a poem entitled "And have no known grave" as his way of coping with his memories.

Leo Harris came from London and was married with no children. His widow married an American serviceman and moved to the USA after the war. We do not know if he has any other relatives, so we may be the only people who remember him. My father died in February 2005.

Aidan Whitfield, May 2007.

In February, nineteen eighty-eight

I stood outside Valetta City Gate

And screwing my eyes up-sun against the light

Beheld a gilded eagle, poised for flight,

Crowning a capital, pinions outspread,

Into the tramuntana turns its tyrant head.

PER ARDUA AD ASTRA, plain to see,

And underneath at 1943, In mute memorial to our glorious dead

One and a half columns I had read

Before, in shock, I saw a name I know

HARRIS R.H.W. F/O.

I shut my stinging eyes and there he stands, Helmet and goggles dangling from his hands,

A fighter pilot to his very roots, From ardent eyes to well-worn flying boots.

He smiles and nods his head as if to say, 'I missed you, Tommy, when you flew away'.

Crouched in our cockpits up to five miles high, We forged our friendship in a hostile sky,

Then parted at Gibraltar; I moved on

But felt, alas, the golden days had gone.

My name I scratch in sand upon the shore;

His name in bronze lives on for evermore.

(Written by T K Whitfield)

"In the autumn of 1941 the fighter Gruppen in France gradually re-equipped with the Focke Wulfl90 which almost totally outclassed the Spitfire mark V— the best aircraft Fighter Command then had operational. The supremacy of the Focke Wulf 190-over the Spitfires lasted untilJuly 1942 when the first Mark IX Spitfires entered service. They were fitted with a Merlin 61 engine that employed a two stage supercharger and had an almost identical performance to the Fw 190".

From "Spitfire A Fighting History" by Albert Price.

In July 1942, 611 Squadron was only the second unit to be supplied with the Spitfire Mark IX. A month later they received a request to provide a test pilot, experienced at flying the Mark IX - because it had been rushed into service without being fully tested. My father volunteered and spent two months with the Intensive Flying Development Unit at Boscombe Down in Wiltshire, before returning to 611 Squadron.

On 7th September he flew up to 42,500 feet but when he returned to base he was annoyed to find that the engineers did not believe him. The next day he repeated the trial with a recording barograph fitted and reached 43,500 feet. It must have been a noteworthy result because he was asked to write about it to the Wing Commander, (see letter). He also helped to develop a new radar that could determine the altitude of approaching aircraft as well as their direction. He flew at a constant altitude, acting as the "target" while the radar engineers calibrated the equipment.

My father's worst day with 611 Squadron was 9th November 1942 when he was shot up and wounded. He kept his bloodstained map as a souvenir (see photocopy right -the airfields are marked with their heights above sea level).

On that day the squadron was flying "Rodeo" 109 and engaged a group of Focke Wulf 190s near Calais. He became detached from the rest of the squadron and was looking at his map to plot a course back to Biggin Hill when he was hit from behind by a short burst of fire. His plane was damaged but he managed to keep flying and crash landed at Hawkinge airfield in Kent, a Forward Landing Ground designated to take damaged aircraft. He was taken to Canterbury hospital where he was the event of the day. Every nurse came to watch as the doctor dug shrapnel out of his left shoulder and side. Six weeks later he was flying again.

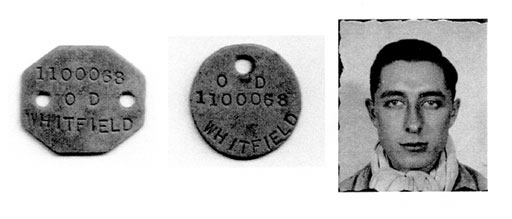

If a pilot was shot down and killed he could be identified by the tags he wore round his neck - one was to be left on the body and the other could be removed (see below).

If a pilot survived being shot down over France he was likely to be captured by the Germans and spend the rest of the war in a prisoner of war camp. If he evaded capture and contacted the French Resistance he might make a "home run" by escaping through neutral Spain to Gibraltar. The Germans had stopped the supply of photographic materials to French civilians which made it difficult for the Resistance to make false identity papers. To aid the Resistance, each airman carried two passport photographs of himself in civilian clothing (see enlargement below).